Bob Erlenbusch is Executive Director of the Sacramento Regional Coalition to End Homelessness and, like House the Homeless founder Richard R. Troxell, he sits on the board of the National Coalition for the Homeless. Currently, in a paper called Homelessness & “Functional Zero:” a Critique, Erlenbusch challenges the validity of the bedrock principles of homelessness policy. (We received the piece from Erlenbusch; it is not, as far as we know, available online.) It appears that some underlying notions seriously need to be re-thought.

The author points out that, lamentably, ten-year plans that started so boldly are now “in their second decade or abandoned altogether.” Strategies that were originally mapped out might need remodeling. For example, when authorities set the triage standards, and prioritized the various arbitrarily-named subgroups, it was decided that the chronically homeless would be dealt with first, then veterans, families, and youth. Of course, any person could belong to more than one of those groups. Anyway, the idea was to eliminate homelessness among one group, then move on to the next. By and large, that plan is not working out as advertised.

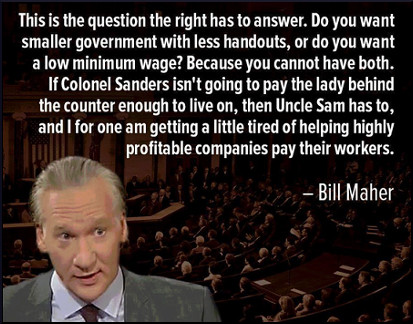

Why have things gone so wrong? For one thing, there’s the minimum wage, which Erlenbusch says “keeps people shackled to poverty.” What does poverty do? The stress of it makes people sick. A chronic shortage of money tempts them to a criminal path. Financial distress breaks up families. Grownups wind up in a hospitals, jails and prisons. Kids wind up in foster homes.

Every year, those institutions discharge thousands of people into homelessness—people who are vulnerable because of poor health, youth who are at risk in many ways, and men and women who are perhaps perfectly capable of supporting themselves, except for being unemployable because of their criminal records. All too often, those jackets are acquired in the first place through crimes directly connected with being homeless—sitting on the wrong bench, panhandling, public urination, and so forth. The vicious cycle that connects prison and the streets (and the foster care system) creates a revolving door that rotates so fast it would make your head spin.

Going farther back, the Reagan administration set the stage for all this in 1980 by making three-quarters of the federal affordable housing budget disappear. Also at some point the mental health system took a dive, which can be blamed on either Reagan or the ACLU, depending on who tells the story. (It might have been both.) All these factors, and more, add up to what Erlenbusch describes as:

…systems and policies that have created three decades of mass homelessness.. Prisons and jails have become the housing for people experiencing homelessness, especially people of color and those with mental health issues.

So now, how do we handle the fallout? For starters, we try to “arrest our way out of homelessness,” and one of the results has been the de facto criminalization of mental illness. (It would be a cliché to invoke the name of a certain World War II military dictator, but his thoughts were on the same wavelength.)

Something else happened, too— what Erlenbusch calls “defining our way out of homelessness.” This trick has been used extensively by bureaucracies full of number-massagers with statistics degrees and flexible principles when discussing, for instance, the unemployment rate. Even when well-intentioned (but ill-advised) people set to work on the definition of homelessness, things can really get ugly.

The Fatal Flaw in Functional Zero

The big fallacy is a concept called “functional zero” and Erlenbusch hopes to inspire a major shift in the thinking behind it. Here is the gist of his argument:

Basically, a community can still have 10,000 homeless people, for example, but if that community can say the number of people entering homelessness is equal to the number exiting, they have reached “functional zero”—forget the 10,000 languishing on the streets and in shelters…

An analogy: say a person weighs 800 pounds. If he ingests 2,000 calories worth of food per day, and moves around enough to burn 2,000 calories in a day, you could say his intake/output ratio is at “functional zero.” Yeah, but he still weighs 800 pounds! This falls under no one’s definition of health. Erlenbusch goes on to say:

It is harmful because when politicians and community members hear “zero”—they hear we have ended homelessness… Then when it is time to allocate scarce public resources it would not be unreasonable for the public and/or elected officials to argue we don’t need as many resources for homelessness because we have solved it! Yet we know nothing could be further from the truth.

Philosophical Background

One excellent point made by the author is that, just like “no means no,” zero should mean zero. In order to grasp the insidious damage done by the “functional zero” doctrine, we relate one of Erlenbusch’s statements to a few other quotations and ideas. He says that because of this convention, “…hundreds of thousands of people experiencing homelessness have remained invisible to our leaders at all levels.” He quotes Marc Uhry:

When people are invisible, you can’t find a solution because you don’t see them.

In The Transformation, George B. Leonard wrote:

One of the most powerful taboo mechanisms is simply not providing a vocabulary for the experience to be tabooed.

The venerable Illuminatus! Trilogy gave us the word “fnord,” which has to do with things that are apparent but indefinite; and the ability to see truths that most people can’t; and being forcibly conditioned to fear that seeing. It might even bear some relationship to what Obi Wan Kenobi famously said: “These aren’t the droids you’re looking for.” It’s about mental judo. Community Solutions defines functional zero like this:

At any point in time, the number of people experiencing sheltered or unsheltered homelessness will be no greater than the current monthly housing placement rate for people experiencing homelessness.

Our minds can be clouded to think that makes sense. But it doesn’t. That definition merely describes homeostasis, or maintenance of the status quo. In any case, those things are not necessarily good, and in this case, they are definitely bad. The definition is, at best, meaningless jargon, and at worse an evil gimmick. It signifies no more than treading water, or running in a hamster wheel—with the appearance of activity but no real progress.

Of course, that’s not entirely fair either. Even when the math is from Alice in Wonderland, every time an individual or family receives help from any agency, it’s a step in the right direction. As in the oft-repeated starfish story, “It made a difference for that one.”

Source: “Topic: Reagan kicked people out of institutions,” Snopes.com, 02/05/06

Image by Bill Maher